Synchronous / Asynchronous: It’s AND not OR

At the 1EdTech Learning Impact conference earlier this month (StrongMind was a sponsor and organized a panel discussion), plenary speaker Phil Hill talked about the idea that pre-COVID, well-designed online learning was understood to mean asynchronous mostly if not entirely.

What a difference a pandemic makes.

During the pandemic, most districts shifted to emergency remote learning for some amount of time, which varied by district and by state. While teacher and district leaders made heroic efforts to deliver instruction while schools were physically closed, by most accounts, pandemic-related remote teaching was inconsistent at best. One of the reasons was that, with little time to prepare, most teachers tried to shift their lectures to online via real-time video, imitating their onsite approach instead of redesigning courses for the online environment. In the worst examples, this meant students watching video lectures for many hours a day. In the moment this was sometimes the best that could be done, but nobody thought it was a good idea. Experienced online educators would talk about how their pre-pandemic courses and schools relied almost entirely on asynchronous instruction, using recorded videos, text, graphics, and other digital content, combined with communication primarily via email and discussion boards.

But then things took an unanticipated turn…the pre-pandemic online schools and course providers began to realize that in fact many students liked having some real-time video interaction with their teachers, and with other students.

These schools rarely had students join hour-long lectures. Instead, they started using video to deliver support such as real-time tutoring, elements such as yoga, and similar interactions that ranged from entirely academic, to entirely social, to a mix of both. Now, post-pandemic, they are finding that blending synchronous and asynchronous instructional strategies produces a better outcome than either modality alone.

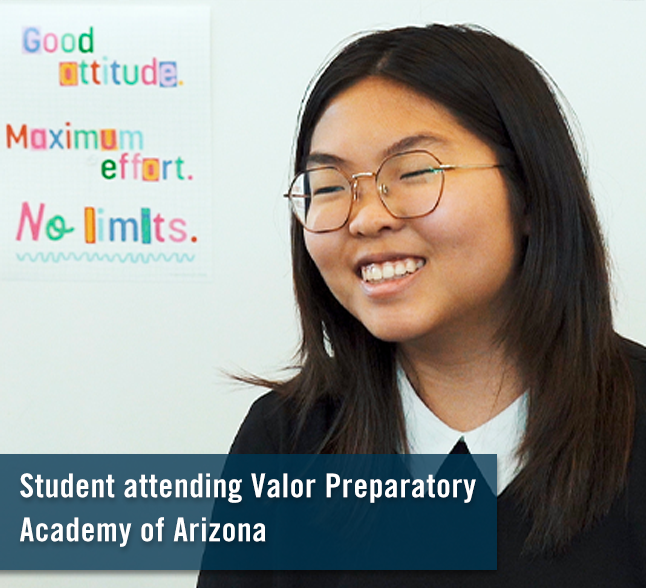

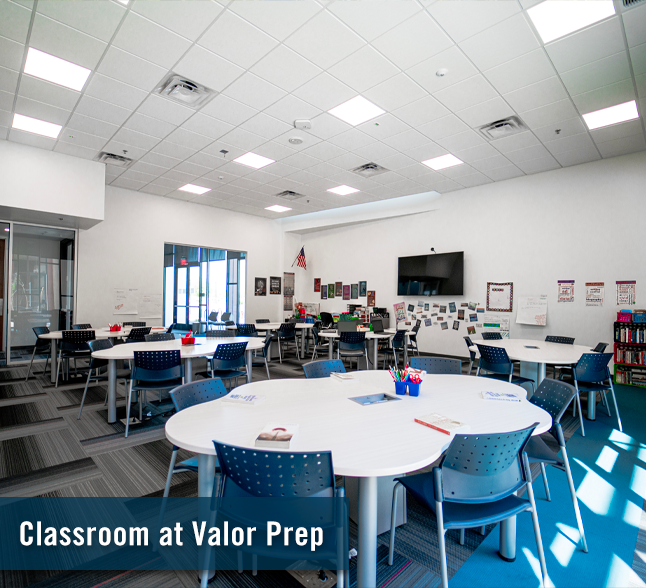

One such blend was discussed at 1EdTech Learning Impact by Dan Mahlandt, principal at Valor Preparatory Academy of Arizona. Dan explained how his instructional model leans heavily on digital content from StrongMind — which is delivered asynchronously — to “set an instructional floor.” Students learn basic concepts via text, graphics, recorded video, animations, and other digital materials, and may demonstrate proficiency via assessments in the learning management system. Teachers work with students in real-time to help them “reach for the instructional ceiling,” which may include working with student directly in areas they are struggling, or pushing them towards more challenging areas.

Valor Arizona is a hybrid school, which means that much of the asynchronous instruction takes place at a distance, and much of the synchronous instruction takes place face-to-face. But synchronous and face-to-face are not synonyms; all online schools and many hybrid schools deliver synchronous instruction using video. In fact, some districts and states are now recognizing that real-time instruction and support can be delivered very effectively at a distance, and eliminating face-to-face instructional requirements while keeping real-time requirements.

What does this look like in practice in an online school? Specific combinations of asynchronous and synchronous interaction are endless, but some elements and examples might include:

- Required synchronous check-ins with students (and parents of younger students) at regularly scheduled times one to three times per week—or maybe as often as once a day, with exceptions when the student or family has a conflict. The check-in may be conducted by a counselor or coach, to discuss how the student is feeling about her progress across all of her courses.

- Optional real-time social interactions, such as story time for younger students, or clubs for older students.

- One-on-one tutoring or small group academic support in a specific class or perhaps even on a specific topic. A teacher might for example see that many students in her math class are struggling with quadratic functions, and offer a time for any students to join her for extra help. The teacher might make this a requirement for students who have not passed a quiz on this topic.

- Video-based book discussions or debates in which students lead the conversations.

All of these options and requirements might add up to 5-10 hours per week. At the other times, students are engaged in several types of activities:

- Reading, watching recorded videos, perhaps working with physical materials in home-based science labs, or even (for older students) taking part in other activities such as academic pursuits or internships that may carry credits.

- Taking assessments and/or writing papers, creating presentations, and recording videos to demonstrate skills and knowledge.

- Communicating with teachers and other students by email and on discussion boards, for example exploring literary themes for an English class.

These are all options; there’s not a recipe or algorithm that most schools follow. But post-pandemic, most online schools are combining asynchronous and real-time instruction and interaction to maximize online learning for students. Valor Preparatory Academy of Arizona is one example of a school that leverages the strength of both technology and teachers for a blend of asynchronous and synchronous learning. Students get more flexibility and agency in their learning while still enjoying a structured and supportive learning environment.